I Could Hear Voices Whispering From the Old City Walls

Pain forever resounds through the streets of Jerusalem…yet, so does love

This is a guest post from Sally Prag who can read more on Substack with her newsletter.

Time to CELEBRATE!

In honour of my birthday landing on Good Friday for the first time in my life…not only have I begun a production line of Israel’s 296,002 greatest hero in action figure form - Reuben Salsa with Flaming Matzah Ball (limited edition) - I’m also offering 50% off all paid yearly subscriptions!

Action Figure not included.

This offer is valid for ONE WEEK ONLY! Click on the button below and subscribe!

All future stories written by Reuben Salsa (every Thursday, 9 am Auckland time) will be for paid subscribers only. Guest posts will remain free and posted every Sunday (9 am Auckland time).

For more articles by Jewish authors, subscribe to the JPF on Medium (click on the image below).

I Could Hear Voices Whispering From the Old City Walls

I couldn’t deny I was nervous. I was heading to Jerusalem with my South African friend, Lucy, and her Israeli boyfriend, Eitan.

Jerusalem itself didn’t make me nervous. I’d been there plenty of times with my parents as a child on our visits from the UK. We’d often take day trips from Tel Aviv where we would stay with my grandmother, whose apartment was just a stone’s throw from the incredible beach that stretches all the way from the northernmost part of the city to Yafo, or Jaffa as it’s called in English, at the southernmost end. One of my mother’s good childhood friends lived among the city sprawl of Jerusalem — in the new part built for the growing population — so we would either visit her, or we would be taken to see the sights of the Old City.

Jerusalem, for me, was a place of firsts. It was the first place I ever ate an entire salad, age nine, despite having been a right little fusspot as a child. My mother was so delighted that she asked the restaurant for their dressing recipe, and that dressing became a staple in my home, forever being known as ‘Jerusalem Dressing’, and turning my dislike for all vegetables into a love affair with salads.

Jerusalem happened to be the place where I first felt spooked by hostility, when my dad and I took a day trip in a hire car, parked it outside Herod’s Gate by the Muslim Quarter for the day, and later returned to find it had been picked up and rolled by a group of local Arab men. I never knew whether they did it because they were hostile to tourists or hostile to the car rental company, being Jewish-owned. Thankfully, the car rental company were very understanding and didn’t make any issue of their now hopelessly bashed-up car.

It also happened to be the first place I spent Christmas Day without my family. Christmas was hardly a big thing for the Jewish family I came from, but there in Jerusalem, Christmas mattered. Of course, the tour operators were all trying to muster up business for their Christmas Day tours to Bethlehem, which was not restricted by checkpoints at that time. A bunch of people I had travelled to Jerusalem with decided to head over to Bethlehem for the day. Personally, being entirely uninterested in looking at a replica of a stable from nearly 2,000 years earlier, and being tired of the cold of Jerusalem in winter by that point, I decided I’d hop on the bus back to my beloved Tel Aviv, the place filled with a bottomless chest of memories, and the place I called home for that moment in my life.

On this particular trip, the reason I was nervous was because Lucy and Eitan were taking me right into the heart of the Muslim Quarter, and to an Arab-owned eatery.

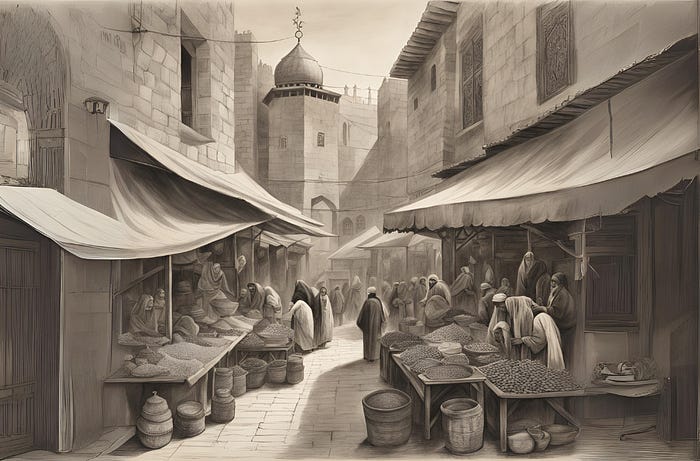

As we entered through Damascus Gate, I swear I could hear voices coming from the walls, warning me away. Whose these voices were, I tried to figure out. Were they the voices of my ancestors who came to live in Jerusalem in the early 1800s, or from all those years earlier, before Jews were banned from Jerusalem? Were they the voices of the many ghosts of millennia gone by? Or were they simply the voice of my mother, who had always drummed into me the ‘great divide’ between the Arabs and the Jews, and how she had grown up acutely aware of hostility? Even exposed to it, for she was just nearing the end of her military service when the Six Day War broke out and her unit’s role was to warn the Israeli Air Force of approaching enemy planes from her placement in the radar control tower in the Negev.

But Lucy and Eitan had gone on and on about how wonderful the food was at this little eatery, and so I didn’t dare oppose the decision to head there.

Within moments, my trepidation was soothed. Rather than tentatively approaching the young brothers who owned the restaurant, Eitan ushered us in and we were immediately welcomed and guided to sit down at a table. Eitan and the one brother in the front of house greeted one another like old friends, and chatted away in a combination of broken Arabic and broken Hebrew.

Here sat two men, supposed sworn enemies, who, at least at that moment, were interested in nothing other than their shared humanity and the willingness to communicate in one another’s languages. There was no anger and no hatred whatsoever, just curiosity, friendship, and a hunger for connection.

Did my mother have any clue that this kind of thing was possible? Was the Israel she’d grown up in a completely different place from the Israel that had evolved since? Likely, since much had changed in the years between when she and my father left Israel to raise their family in the UK, and those months I spent in Israel as an 18-year-old in late 1993 and early 1994. And much more would change in the years that followed.

There’s a Jewish American writer called Sarah Tuttle-Singer whose writings I love to read. After a visit to Israel at age 16, she fell so hard in love with the country that she vowed she would move there one day. And she did, right into the heart of the Old City, at the intersection of the four quarters.

In the introduction to her book, Jerusalem Drawn and Quartered, she describes her favourite street which is also right beside where she now lives. The street, with two names — one in Arabic and one in Hebrew — is a place that has seen horrific quantities of blood spilled, including her own when, at the age of 18, she was stoned by a Palestinian youth. It was an experience that nearly terrified her enough to never return, but not quite. The allure of the city was too strong to let fear prevent her return.

As she describes the street and the many acts of violence it has seen, from Border Police brutality to terrorist attacks on Jews, what is most striking is that, no matter how much fury is unleashed, there is never a shortage of love and compassion that keeps shining through. Such as the time her 19-year-old Palestinian friend was beaten up by a policeman because his papers had expired the previous week. Yet, by the time he was done kicking the shit out of him, it was the policeman who was crying tears of remorse and pain for what he’d done.

As she finishes telling us about the two Jewish fathers who were left to bleed to death on that street while their terrified wives were kicked and spat on, she then shares the story of a kitten, rescued and passed to her by Palestinians in the Muslim Quarter and then adopted by a woman in the Jewish Quarter. To this day, she is asked daily after the health of the kitten by Border Police, Yeshiva kids, Palestinian merchants, and even a priest.

She says,

It’s my favourite street because it is an injured artery from Jerusalem’s holy heart to the rest of us, and terrible things have happened, but lovely things have happened too.

And it’s the street that I walk the most, because if you expect to find a miracle in Jerusalem, you have to start looking in a place like this where all roads — beautiful and terrible — meet. — Jerusalem Drawn and Quartered

Today, she lives in a building shared by Jews and Arabs. I have read her accounts of how they sheltered together in the stairwell when IRGC sent 300 drones and missiles over to Israel from Iran in April of this year. No one ethnic group was safer than another at that moment. But are they ever?

The difference is that inside the borders of Israel proper — excluding the West Bank, or Judea and Samaria — no matter the religion or the ethnicity, they are, together, a targeted people. And now more than ever, as long as they can bear to, they must lean on one another.

I don’t know if all Arab Israeli citizens have fully accepted Israel as a legitimate country in its own right, but the vast majority have, and they are grateful for their Israeli citizenship, seemingly more so since the October 7th massacre last year. Nowhere else in the Middle East can Muslim women become surgeons in Jewish hospitals, or judges in Jewish courts of law. In many parts of Israeli society, Jews and Arabs work alongside one another, serve one another, learn alongside one another, and defend the country alongside one another.

As one British peace activist explained following his visit to see Israel, excluding in the West Bank, Muslims and Jews co-exist in Israel far more successfully than they do in the West. According to him, Israel, for all of its faults, has had enormous reason to create equality of rights between the different ethnicities. It’s not perfect, but the integration between Muslims and Jews is far more advanced than many are given to believe, and far more advanced than Western democracies have achieved.

Something about it just works, despite the many years of hostilities and bloodshed. Perhaps members of Israeli society have been fast-tracked into an evolving awareness that peace must start with oneself and one’s choices.

Back to that eye-opening moment in the Arab eatery in the heart of the Arab Quarter of Jerusalem, slowly my armour began to peel away. Fear that had been instilled into me was gradually falling to the ground, helped along by the delicious food I now had on the table in front of me.

Felafels, pickled gherkins, chilis and olives, mounds of houmous and tahina, and piles of round pittas had my mouth watering. We munched our way through this incredible spread that, to me, had only been matched by the Jewish Yemenite restaurants in the Shuk Ha-Carmel in Tel Aviv.

Here in this little eatery, we were experiencing an exchange of energy on a grand scale, and gratitude in abundance. Our Arab hosts were smiling in delight at our enjoyment, and we fed off their delight as much as we were nourished by the food they had prepared for us.

Upon paying our bill and then some in tips, and thanking them profusely, we left and wandered the streets of the Arab Quarter, marvelling at the antiques and beautiful woven rugs from times long past, when peace may not have been balancing so precariously on a knife edge as it was now. We were met almost exclusively with smiles and kindness. I say almost because not everyone is ready to trust, or has reason to trust, just as I hadn’t yet before we sat down in that magical little eatery. But almost was enough for us on that day.

There’s an indentation in one of the walls of the Old City that is said to have been left by Jesus when he stumbled and almost fell on his way to being crucified. It’s an indentation that symbolises pain of the worst kind — betrayal and cruelty. Yet over the years that have passed since visitors began paying homage to Jesus in Jerusalem, that indentation has continued to be worn down, not by the pain of betrayal, but being touched by hands of love and devotion.

That day, the voices of fear that had whispered to me upon entering the Old City of Jerusalem transformed into voices of love, of connection, and of longing for better times.

I believe everyone can hear them when they stop and listen for long enough. But not everyone is willing to.

Not yet, at least.

Such acceptance, understanding and peace, strong but fragile enough to be shattered by a single word or by a single person. Am Yisrael Chai

It's been more than forty years since I visited Israel for the first time. Stepping onto the ground at Ben Gurion Airport, I felt a profound connection to Israel. I have not been back since the mid 1980s, but that feeling has never left me.